TL;DR

This research covers the analysis of Frame Counting, postMessage broadcasts, and browser features among XS-Leaks vulnerabilities.

Frame Counting is one of the representative XS-Leaks techniques that enables inferring sensitive information through side-channel attacks without bypassing the Same-Origin Policy. While it appears in CTF challenges, it’s also a real-world problem with significant impact and risk.

Facebook (Exposed Private Information), Github (Exposed Private Repositories)

postMessage broadcasts will be briefly introduced here, with a more detailed explanation of postMessage planned for another article. Browser features are security implementations introduced to mitigate vulnerabilities, which are still being discussed and developed. We’ll explain the standard implementation and details, and also explore how browser features introduced to prevent vulnerabilities can lead to other vulnerabilities.

Frame Counting

Concept

Frame Counting is a technique for obtaining sensitive information through window.length without bypassing Content Security Policy when it’s configured. There are two methods for loading new windows: using window.open() and <iframe>.

When accessing other pages opened through window.open() or <iframe> in a cross-origin environment, access is limited to restricted properties according to HTML specifications.

(Reference) HTML Spec

1 | 7.2.1.3.1 CrossOriginProperties ( O ) |

Among these, the win.length property provides information about the number of iframes directly loaded in the window object.

1 | <iframe src="https://example.com" width="400" height="200"></iframe> |

For web pages where the number of iframes changes according to specific conditions, this property can be used to reverse-engineer the user’s state. This provides attackers with a meaningful information leakage path.

Difference between window.open() and iframe

To successfully perform attacks using Frame Counting, it’s necessary to understand the detailed differences between window.open() and <iframe>. If a vulnerability has been confirmed but exploitation isn’t working well, the following content may be useful.

Impact of SameSite Cookie (Lax) Policy

When the SameSite attribute is set to Lax, third-party cookies are only sent for Top Level Navigation (when the entire window moves to a different URL in a GET request). Therefore, using <iframe> may not work properly.

User Click Required

According to MDN documentation, “Modern browsers have strict popup blocking policies, so popup windows should only open after direct user input, and each window.open() call requires separate user interaction.”

This can be an important constraint when solving CTF problems created with puppeteer, etc.

Bypassing Framing Protection

Framing Protection is a security technique that prevents web pages from being included in <iframe>, <frame>, <embed>, <object>, etc. Since many XS-Leak attacks utilize these framing features, blocking them can prevent attacks. This can be applied through X-Frame-Options and frame-ancestors in Content-Security-Policy.

1 | X-Frame-Options: deny |

iframe sandbox attribute

| Attribute Value | Description |

|---|---|

| (empty) | Applies all restrictions. |

| allow-forms | Allows the resource to submit form data. |

| allow-modals | Allows the resource to open modal windows. |

| allow-orientation-lock | Allows the resource to lock screen orientation changes. |

| allow-pointer-lock | Allows the resource to use the Pointer Lock API. |

| allow-popups | Allows popups like window.open() or target=”_blank”. |

| allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox | Allows opening windows that don’t inherit restrictions when opening new windows from a sandboxed document with all restrictions applied. |

| allow-presentation | Allows the resource to start presentation sessions. |

| allow-same-origin | Allows the resource to be treated as if it passed the same-origin policy. |

| allow-scripts | Allows the resource to execute scripts but prevents creating popup windows. |

| allow-storage-access-by-user-activation | Allows the resource to request access to parent storage features using the Storage Access API. |

| allow-top-navigation | Allows the resource to navigate the top-level browsing context (_top). |

| allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation | Allows the resource to navigate the top-level browsing context (_top) only when requested by the user. |

Case Study - Exposed Private Information (Facebook)

Reference: https://www.imperva.com/blog/archive/facebook-privacy-bug/

In May 2018, a user private information leakage vulnerability using Frame Counting technique was reported on Facebook. This was not just a simple proof of concept but a major security incident that occurred in an actual large-scale service.

Facebook’s search function responds with search results in iframes. At this time, the number of iframes included in Facebook search results could be used to infer whether specific information exists. Attackers could use this to leak the following information:

- Friend relationship status with specific users

- Membership status of specific pages

- Public/private status of personal profiles

- Existence of other personalized information

PoC Video by Ron Masas

The severity of this vulnerability lies in the fact that attackers can leak sensitive personal information without the victim’s explicit consent or awareness. It’s also evaluated as a case that revealed limitations of existing security models in that it can access cross-origin information without bypassing Same-Origin Policy.

In CTFs

Here are Frame Counting related problems that appeared in CTFs.

Facebook CTF 2019 - [web] secret note keeper

Archive: https://github.com/fbsamples/fbctf-2019-challenges/tree/main/web/secret_note_keeper

Interestingly, after Frame Counting attack cases were reported on Facebook in 2018, a related problem was presented in Facebook CTF the following year in 2019.

1 |

|

The /search?query= endpoint loads iframes according to the number of searched notes, so Frame Counting technique can be used.

1 | ... |

ASIS CTF Finals 2024 - [web] fire-leak

This is an advanced problem that applies Frame Counting and other techniques, requiring advanced attack techniques that combine ReDoS (Regular Expression Denial of Service) and Frame Counting.

1 | app.get("/", (req, res) => { |

Attackers can insert HTML, and specific strings are filtered. CSP (Content Security Policy) is strongly set to 'none', fundamentally blocking traditional XSS attacks including script execution.

The {{TOKEN}} syntax included in the inserted HTML is automatically replaced with the req.cookies.TOKEN value on the server side, which means the admin’s authentication token.

1 | // Issue a new token |

The admin token is set every time it’s reported to the bot.

To leak req.cookies.TOKEN, you need to solve using Side Channel rather than XSS.

The author (Ark) utilized <input pattern="..." value="...">.

1 | <input |

This shows a sophisticated attack technique that uses the <input pattern="..." value="..."> structure to cause time delays through ReDoS and leak tokens by utilizing differences in iframe.length change times.

postMessage Broadcasts

Concept

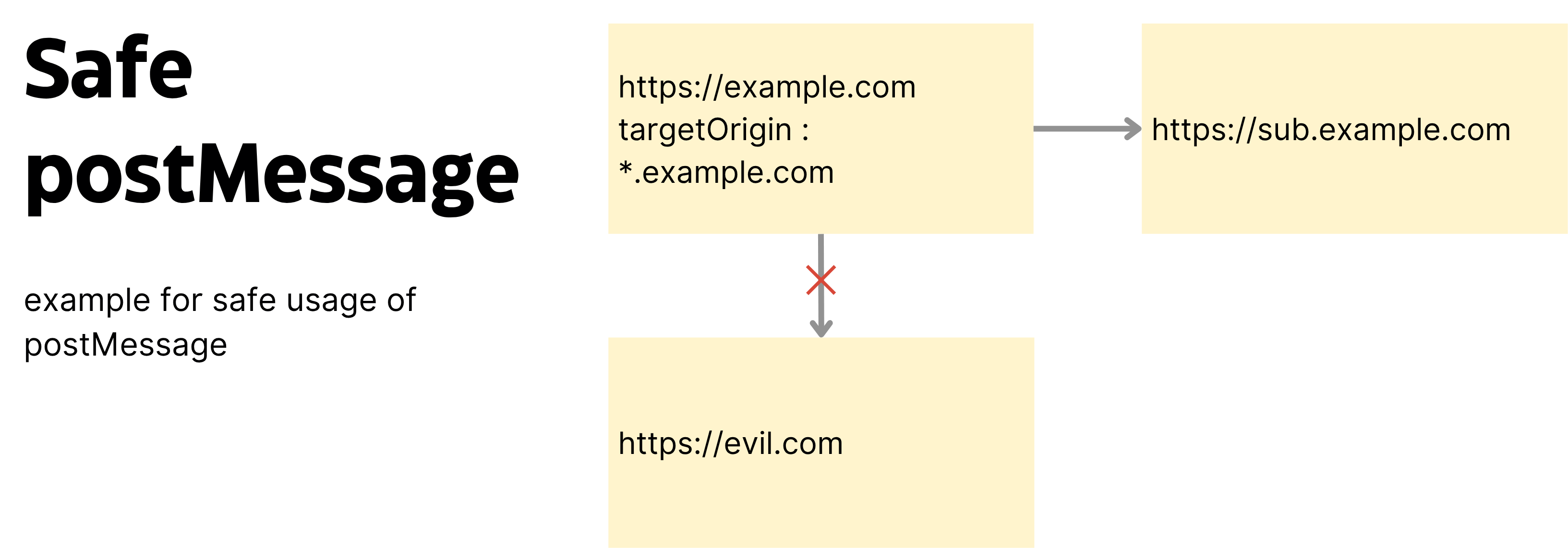

postMessage is a web API designed to safely deliver messages between different origins. This API was designed for secure communication in Cross-Origin environments and provides the ability to selectively send messages only to allowed Origins through the targetOrigin parameter.

However, postMessage has other vulnerabilities and vulnerable implementations, which will be covered in another article.

Browser Features (CORB, CORP)

Both CORB and CORP are security implementations introduced to mitigate security vulnerabilities and are features still being discussed and developed. However, these two security policies have created new vulnerabilities.

In normal usage environments, developers explicitly set targetOrigin to restrict message transmission only to trusted domains. However, due to mistakes during development or lack of security awareness, cases where targetOrigin is set to wildcard (*) or not set at all frequently occur.

.png)

When such vulnerable implementations exist, attackers can send malicious messages from unauthorized Origins to the victim’s browser or intercept messages containing sensitive information. Particularly when messages contain user authentication tokens, personal information, or application internal state information, it can lead to direct security breaches.

postMessage-related vulnerabilities can develop into more complex and dangerous forms through not only simple targetOrigin configuration errors but also absence of message validation logic, processing messages from untrusted sources, and connections with other web vulnerabilities. These advanced attack techniques and vulnerable implementation patterns will be covered in detail in separate in-depth analysis.

Browser Features (CORB, CORP)

CORB (Cross-Origin Read Blocking) and CORP (Cross-Origin Resource Policy) are both security mechanisms introduced by browser vendors to mitigate existing web security vulnerabilities. Both policies aim to prevent information leakage and side-channel attacks that can occur in Cross-Origin environments, and belong to evolving security features that are still under continuous discussion and improvement.

However, unexpected side effects occurred with the introduction of these security policies. An ironic situation arose where security mechanisms designed to solve existing vulnerabilities created new forms of vulnerabilities themselves. This is a phenomenon also called the “security feature paradox” in the security field, where attempts to strengthen security create other attack vectors.

Vulnerabilities occurring in CORB and CORP are not high-risk vulnerabilities that directly compromise systems or leak critical data. However, these vulnerabilities provide attackers with indirect information leakage paths and form important side channels that can be utilized especially for fingerprinting or inferring user browsing patterns.

The fact that security policies themselves can be used as attack tools raises fundamental questions about security design philosophy beyond simple technical issues. The fact that mechanisms introduced to strengthen security become causes of other vulnerabilities provides very interesting research topics for security researchers, and this is a representative case showing the complexity and unpredictability of modern web security.

CORB

According to chromium, CORB has the following meaning: (translated by gemini and reviewed)

1 | Cross-Origin Read Blocking (CORB) is a new web platform security feature that helps mitigate the threat of side-channel attacks (including Spectre). It is designed to prevent the browser from delivering certain Cross-Origin network responses to a web page, when they might contain sensitive information and are not needed for existing web features. For example, it will block a Cross-Origin text/html response requested from a <script> or <img> tag, replacing it with an empty response instead. This is an important part of the protections included with Site Isolation. |

In summary, it blocks responses and replaces them with empty responses when appropriate Content-Type is not returned for Cross-Origin requests with nosniff headers. For example, in requests like <script src="/path">, if the Content-Type of the responding /path is text/html, it blocks this and displays the response body as empty.

However, this causes new XS-Leaks vulnerabilities.

The following two scenarios occur, which we’ll examine one by one:

CORBdetection: One state is protected by CORB, the second state is 4xx/5xx errornosniffheader detection: One state is protected by CORB, the second state is not protected

CORB Detection

- An attacker can include a Cross-Origin resource in a script tag that returns 200 OK with

Content-Typeoftext/htmlandnosniffheader. - CORB replaces the original response with an empty response.

- Since the empty response is valid JavaScript, the

onerrorevent doesn’t occur, butonloadoccurs instead. - The attacker triggers a second request (corresponding to the second state) like in step 1, which returns a 4xx/5xx error. At this time, the

onerrorevent occurs.

- 200 + CORB → onload

- 4xx/5xx + no CORB → onerror

Being able to distinguish between these two states causes XS-Leak.

nosniff Header Detection

CORB also allows attackers to detect whether the nosniff header exists in requests.

This problem occurred because CORB is only applied based on the presence of this header and some sniffing algorithms.

The example below shows two distinguishable states:

- When serving resources with

Content-Typeoftext/htmlalong withnosniffheader, CORB prevents attacker pages from embedding the resource as a script. - When serving resources without

nosniffand CORB cannot infer the page’sContent-Type(still maintainstext/html), a SyntaxError occurs because the content cannot be parsed as valid JavaScript. Since script tags only trigger error events under specific conditions, this error can be caught by listening towindow.onerror.

Therefore, the presence of the nosniff header can be leaked.

nosniff Header Detection

CORB also allows attackers to detect whether the nosniff header exists in requests.

This problem occurred due to the fact that CORB is applied only based on the presence of this header and some sniffing algorithms.

The example below shows two distinguishable states:

- When serving a resource with

Content-Typeoftext/htmlalong with thenosniffheader, CORB prevents attacker pages from embedding the resource as a script. - When serving a resource without

nosniffand CORB cannot infer the page’sContent-Type(still maintained astext/html), a SyntaxError occurs because the content cannot be parsed as valid JavaScript. Since script tags trigger error events only under specific conditions, this error can be caught by listening towindow.onerror.

Therefore, the presence of the nosniff header can be leaked.

CORP

CORP stands for Cross-Origin Resource Policy and serves to block resources from being loaded from other origins.

For example, if https://example.com/image.png has Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy: same-origin set:

<img src="/image.png">withinhttps://example.com✅<img src="https://example.com/image.png">fromhttps://attacker.com❌

XS-Leaks vulnerabilities caused by CORP have similar mechanisms to the CORB case. By detecting browser behavior (e.g., whether errors occur, differences in loading times, etc.) when specific resources are blocked by CORP policy versus when they’re not, attackers can leak information. For example, it becomes possible to infer login status or the existence of personalized data by determining accessibility to specific URLs through CORP blocking status.

Review

Through research, we confirmed that XS-Leaks techniques are not just theoretical concepts but realistic threats that can be sufficiently exploited in actual commercial service environments. Additionally, by discovering XS-Leaks vulnerabilities in actual services during bug bounty activities, we also proved that these techniques can act as practical security problems.

XS-Leaks are difficult to detect due to their Side-Channel characteristics, and effective response is difficult with traditional security models alone. Particularly, the ability to infer sensitive information without bypassing Same-Origin Policy (SOP) reveals limitations of existing security systems. Accordingly, sophisticated response strategies are required, including strengthening frame blocking policies (X-Frame-Options, frame-ancestors) and Content Security Policy (CSP).

Additionally, while browser security features like CORB and CORP are effective in blocking specific attack vectors, they can become clues for new side-channel attacks when misconfigured or under specific conditions. Detailed review and testing should also be conducted in the design and application of security features.

Consequently, XS-Leaks is still a developing area, and due to its complexity and flexibility, it approaches attackers as a useful tool and defenders as a security challenge to solve. Along with preparing practical countermeasures, it’s most important to increase related understanding through continuous learning and practice of the latest technology trends.